"The number of

latches confused her and warned her

"but Chintana didn't know what to do

with warnings anymore.

It took me roughly half an hour to figure out that The Fifty Year Sword, by Mark Z. Danielewski was a poem, auspiciously packaged as a novella. Before you rush to judgment, I should say, it took me the better part of an otherwise total success of a fundraiser to put together that Mojitos call for lime, as opposed to any other variety of citrus fruit. Point is, if isn't written on the outside or doesn't come wrapped in an outside, who's to say? I'm not a mind reader, people! Or a book reader, for that matter.

Once I had, however, it both made sense and surprised me that I'd read the first 100 pages without blinking an eye or updating my Pinterest account, so to speak. That's what language full of rhyme and fog and rhythm does: it keeps one busy looking out for pattern like a tool for lexical survival and in doing so makes that which it's conveying less a cerebral fiction than spontaneous event to be believed or not, enjoyed or not and, in the case of poetry, comprehended, period. But always shared, or at least felt to be. Incidentally, that's what leaving every even numbered page blank in your book does, too. Granted, most of those house drawings.

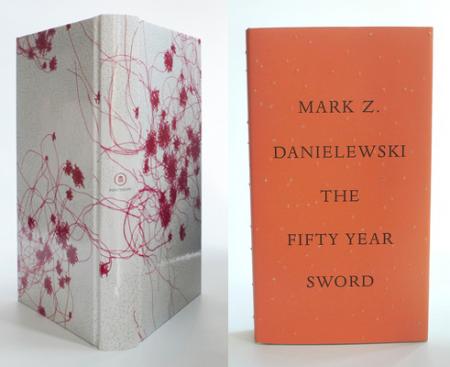

"Feeling" is an operative word for talking about The Fifty Year Sword. The book itself is a pleasure to feel, its cover pricked with pin-sized holes, its size comparable to a takeout menu (the deluxe version, out next month, in a box designed to replicate the one the story's "storyteller" has in tow on Halloween, is a pleasure even to open). Its contents too are felt, I'd argue, more suddenly or seamlessly, as if physically incurred, by nature of their being frightful and written in response to a culture that insists we recognize fear as an immediate matter of fact before disappointment or joy.

That said, The Fifty Year Sword is a book written to be read, not shied or humiliated away from. And like all scary stories, best read aloud in the company of others, ideally on Halloween night, when this story about a story takes place. Calling it a scary story, however, is like calling coffee hot. I appreciate the warning, but I'm also not a sadist looking for a good time. I'm a reader. There's a difference. In other words, I want to know what else it's got. And you should, too, because the book wants you to know, or rather, wants you to want to know. (I'm trying. I'm trying really hard to make a joke about Cheap Trick.) So much so that it keeps its contents hidden, formally in verse (although I like to think of poetic verse and meter and as a means of expanding on and appealing to rather than trophying what can be called experience) and literally in terms of whatever is inside the box and, for that reason, most on reader's minds.

Not knowing, however, will give you a clue,

if not about the story then yourself, specifically in regard to who you are as

a reader. When the "what" is kept a secret, the "why" is

rife with implications about narrativity's potential and its limits, and our

own, in terms of what as readers we deserve. Depending on your outlook, and

perhaps whether you're a plastic jackolantern half-empty or half-full kind of

person, you will pick up this "novella" and decide you're being taken

for a ride or that, finally, a writer's trusting you to go on one alone, to

scare and turn the pages for yourself. If I've made it sound like work, it's

not. And anyway, there's always a new Paranormal Activity showing I'm sure somewhere nearby.

No comments:

Post a Comment