Friday, May 17, 2013

TO-READ l Airmail

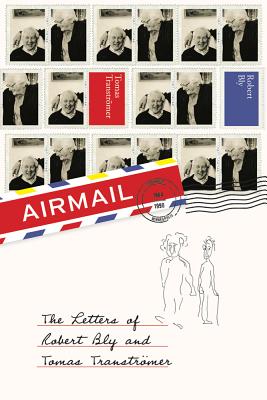

A few weeks back I wrote about the poet Christian Wiman's meditation on belief, and once again, I find myself drawn to a book about a poet that's not poetry. Actually, it's two poets. And, truth be told, Airmail is full of poems sent back and forth between said poets, Robert Bly and Tomas Transtromer. That is, when they're not talking about the 1964 election, or the death of Randall Jarrell, or the birth of a daughter. By the way, why is it that we caution ourselves from poets with the title, while novelists and memoirists and famous chefs stay, simply, "authors"? Is it the worry that a poet might actually open the door of a moving vehicle while a novelist, at worst, might base a character's penchant for cursing on your road rage? (One good for nothing poet makes a joke about free will that doesn't play and has to ruin it for everybody.) Hmm? Oh, nothing. I thought you said something. Ha. Funny.

You could look at Airmail as a collection of poems with extensive background notes, but it is, in fact, or in guise, a collection of letters; the letters of two internationally acclaimed poets who after, by chance, checking out each others' books at the same time (Bly coming home from the University of Minnesota library with a copy of Transtromer's The Half-Finished Heaven in hand only to find a letter waiting for him from Transtromer himself) started up a correspondence that would last for nearly thirty years. With more than 290 letters in tow, Airmail more than represents the baggage of both poets' concerns, from the war in Vietnam--which Bly rallied against in the poems that he wrote and those he published in his magazine, The Sixties, and in co-founding American Writers against the Vietnam War--to the daily struggles of living a life that affords time to write as well as eat, pay bills, and travel. Which isn't to say that Airmail documents a time when either Bly or Transtromer were nobodies. Though the poets' friendship took off before Bly won the National Book Award, and nearly 50 years before Transtromer won the Nobel Prize, becoming something of a household name, both poets were well established in their respective countries. Thanks, in no small part, to Bly and Transtromer's concomitant commitment to translating each others' work, the ins and outs of which are on display and irresistible for anyone interested in the intricacies of a poem's, much less a translation's, evolution, Transtromer's is now a face of poetry in America, just as Bly, presumably, is recognized in Sweden.

So, that's the big idea. But as in all art it's the little ones that do and should take shape. As Transtromer writes, referring to the lack thereof in several of his contemporaries' politically astute polemics: "They drape themselves in an attitude instead of giving form." And not surprisingly, the form of these letters--indeed, the form of letters, period, or semicolon, depending--is what gives readers the sense that we are in on the conversation. And not in some scandalous, drug-addled, out of depth look into Robert Bly's sock drawer sort of way, but as if coming across ideas and information for the first time: conversations unrecorded, works in progress, words unmeant and pardoned. A pensive spontaneity seems to be what Transtromer and Bly had in mind when they began their correspondence; a practice that with luck and time might grant their poems, and their lives as poets, a kind of validation no reward could supplant; that of close reading and acceptance, in the sense of being given, not just baited. "What makes translating SNOWFALL so worthwhile," Transtromer writes, "is that the poem will strike Swedes as completely natural--a good reader knows that this isn't an exotic product by some American but I have experienced this mystery for myself." Likewise, as Thomas R. Smith notes in the book's introduction, Transtromer's letters were as sparsely edited as possible so that we "may enjoy [them] as Bly first did." (Just now, for instance, I could have sprung the label "editor" on Thomas R. Smith's name, but did I? No. Because no one thinks Thomas R. Smith is capable of sleeping with your best friend and, literally, forgetting all about it.)

Now me, I don't even answer the door unless someone is pressing record. And though a reader has to wonder whether two of the world's most famous writers saw their exchange as a potential intellectual artifact, as a certain, recent publication seems wont to assert, all signs point to, if not the opposite, a general disinterest in embellishment and voyeurism in favor of a drawing back, again, in terms of shedding their personas and in effort to delimit and refortify their work (i.e., at no point does Transtromer take advantage of the opportunity to ask Bly why he thinks he's the "only poet worth reading in North America" or "what gives [his] hair such volume"). "Other translators give a pale reproduction of the finished poem," writes Transtromer, "but you bring me back to the original experience." Originality is what we addict for in works of art like these; a starting point from which to base what we consider to be easy, though intangible, works of the imagination; plumes of time intensive smoke that slowly rise up from the ashes of experience and go on to shape a writer's legacy, while staying secrets even the most articulate of authors often can't, or won't, explain. We want answers. Damnit! (Eh, just trying it on.) Yet letters, journals, prison scrawls, etc., more than remnants scattered across the literary landscape for posterity, remind us that no book or poem is a relic but a product of exchange. And not a consumer product, either. Ha! There! One for poets! Two for the uncle who didn't order pizza at Thanksgiving and pretend not to be home. But one for poets!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment